- Solutions

Use Cases

Initiatives

Technologies

Industries

RouteRoute data to multiple destinations

EnrichEnrich data events with business or service context

SearchSearch and analyze data directly at its source, an S3 bucket, or Cribl Lake

ReduceReduce the size of data

TransformShape data to optimize its value

StoreStore data in S3 buckets or Cribl Lake

ReplayReplay data from low-cost storage

CollectCollect logs and metrics from host devices

Universal ReceiverCentrally receive and route telemetry to all your tools

RedactRedact or mask sensitive data

Supercharge Security InsightsOptimize data for better threat detection and response

Agent ConsolidationStreamline infrastructure to reduce complexity and cost

Tackle Application Infrastructure SprawlSimplify Kubernetes data collection

Reduce Log VolumeOptimize logs for value

Slash Storage CostsControl how telemetry is stored

Accelerate Cloud MigrationEasily handle new cloud telemetry

Avoid Vendor Lock-InEnsure freedom in your tech stack

AIOps OptimizationAccelerate the value of AIOps

Seamless Integrations to Power All Your Tools See all Integrations - Products

Overview

Products

Services

Cribl Products Overview

Effortlessly search, collect, process, route and store telemetry from every corner of your infrastructure—in the cloud, on-premises, or both—with Cribl. Try the Cribl Suite of products today.

Learn moreStreamGet telemetry data from anywhere to anywhere

Cribl.CloudGet started quickly without managing infrastructure

EdgeStreamline collection with a scalable, vendor-neutral agent

CopilotAI-powered tools designed to maximize productivity

SearchEasily access and explore telemetry from anywhere, anytime

AppscopeInstrument, collect, observe

LakeStore, access, and replay telemetry.

Activation ServicesGet hands-on support from Cribl experts to quickly deploy and optimize Cribl solutions for your unique data environment.

Service Delivery PartnersWork with certified partners to get up and running fast. Access expert-level support and get guidance on your data strategy.

- Customers

Customer Stories

Customer Highlights

Customer Stories

Get inspired by how our customers are innovating IT, security, and observability. They inspire us daily!

Read customer stories

- Learning & Resources

LearningCribl University

FREE training and certs for data pros

Cribl University LogInLog in or sign up to start learning

DocsTech DocsStep-by-step guidance and best practices

Self Guided TrialsTutorials for Sandboxes & Cribl.Cloud

CommunitySlackAsk questions and share user experiences

Curious Knowledge BaseTroubleshooting tips, and Q&A archive

DownloadsDownload LibraryThe latest software features and updates

Past ReleasesGet older versions of Cribl software

SupportSupport PortalFor registered licensed customers

Customer SuccessAdvice throughout your Cribl journey

- Pricing

- About

Cribl

Partners

Find a PartnerConnect with Cribl partners to transform your data and drive real results.

Partner ProgramJoin the Cribl Partner Program for resources to boost success.

Partner LoginLog in to the Cribl Partner Portal for the latest resources, tools, and updates.

- Demos

- Try Cribl

-

Login

-

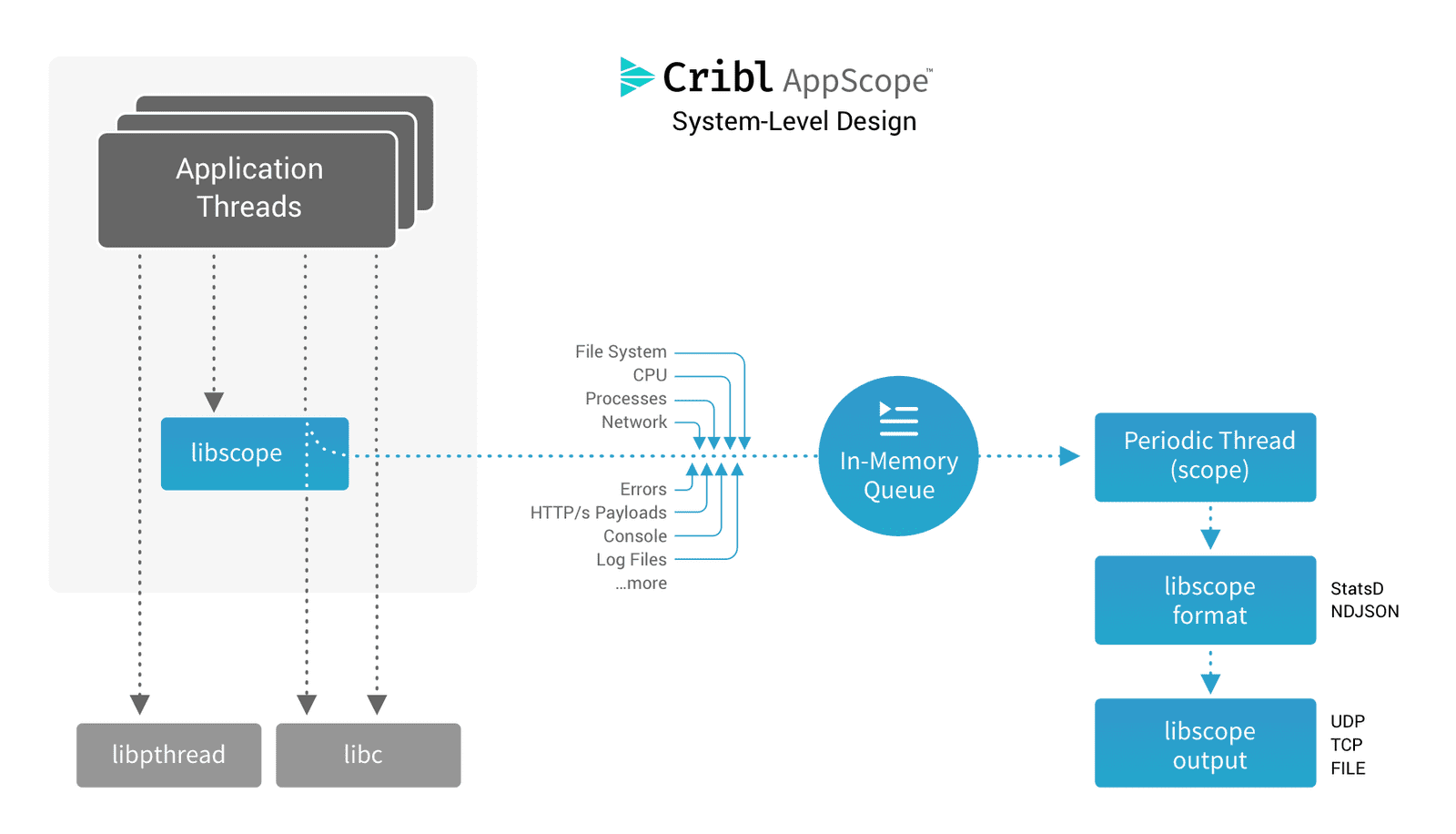

Figure 1.

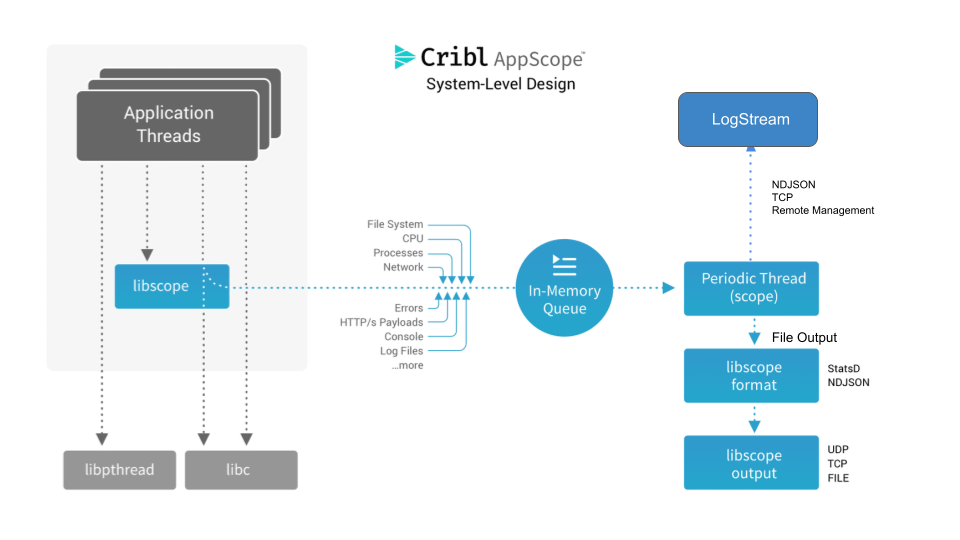

Figure 1. Figure 2.

Figure 2.