-

Products

Product Portfolio

Cribl puts your IT and Security data at the center of your data management strategy and provides a one-stop shop for analyzing, collecting, processing, and routing it all at any scale. Try the Cribl suite of products and start building your data engine today!

Learn more ›

Evolving demands placed on IT and Security teams are driving a new architecture for how observability data is captured, curated, and queried. This new architecture provides flexibility and control while managing the costs of increasing data volumes.

Read white paper ›Cribl Stream

Cribl Stream is a vendor-agnostic observability pipeline that gives you the flexibility to collect, reduce, enrich, normalize, and route data from any source to any destination within your existing data infrastructure.

Learn more ›

Cribl Edge

Cribl Edge provides an intelligent, highly scalable edge-based data collection system for logs, metrics, and application data.

Learn more ›Cribl Search

Cribl Search turns the traditional search process on its head, allowing users to search data in place without having to collect/store first.

Learn more ›Cribl Lake

Cribl Lake is a turnkey data lake solution that takes just minutes to get up and running — no data expertise needed. Leverage open formats, unified security with rich access controls, and central access to all IT and security data.

Learn more ›Cribl.Cloud

The Cribl.Cloud platform gets you up and running fast without the hassle of running infrastructure.

Learn more ›

Cribl.Cloud Solution Brief

The fastest and easiest way to realize the value of an observability ecosystem.

Read Solution Brief ›Cribl Copilot

Cribl Copilot gets your deployments up and running in minutes, not weeks or months.

Learn more ›

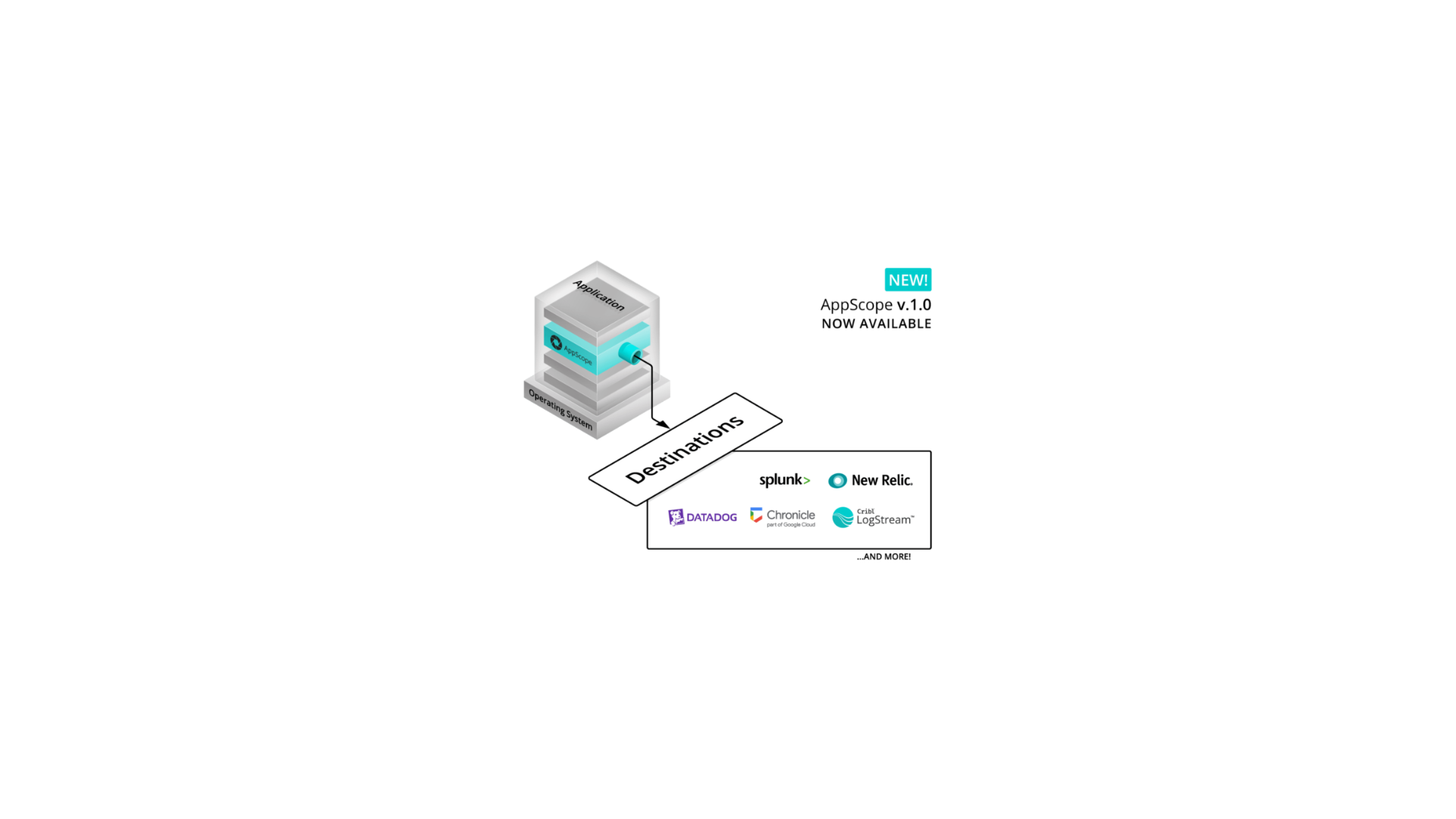

AppScope

AppScope gives operators the visibility they need into application behavior, metrics and events with no configuration and no agent required.

Learn more › -

Solutions

Use Cases

Explore Cribl’s Solutions by Use Cases:

- Supercharge Security Insights ›

- Accelerate Cloud Migration ›

- Avoid Vendor Lock-in ›

- Agent Consolidation ›

- Slash Storage Costs ›

- Free Up Space for High-Value Data ›

- Route From Any Source To Any Destination ›

- Immediate Access to Archived Data ›

- Replay Data from Low-Cost Storage ›

- Reduce Log Volume & Pay Less for Infrastructure ›

Integration

Explore Cribl’s Solutions by Integrations:

Industries

Explore Cribl’s Solutions by Industry:

-

Resources

July 31 | 10am PT / 1pm ET

Navigating the Data Current Report: Transforming IT & Security Operations in 2024

Register ›Learning

Try Your Own Cribl Sandbox

Experience a full version of Cribl Stream and Cribl Edge in the cloud.

Launch Now ›Tools & Pricing

-

Customers

Customer Stories

Get inspired by how our customers are innovating IT, security and observability. They inspire us daily!

Read Customer Stories ›

Sally Beauty Holdings

Sally Beauty Swaps LogStash and Syslog-ng with Cribl.Cloud for a Resilient Security and Observability Pipeline

Read Case Study ›Customer Experience

Learning

Try Your Own Cribl Sandbox

Experience a full version of Cribl Stream and Cribl Edge in the cloud.

Launch Now › -

Company

About Cribl

Transform data management with Cribl, the Data Engine for IT and Security

Learn More ›

Cribl Corporate Overview

Cribl makes open observability a reality, giving you the freedom and flexibility to make choices instead of compromises.

Get the Guide ›Cribl Newsroom

Stay up to date on all things Cribl and observability.

Visit the Newsroom ›Leadership

Cribl’s leadership team has built and launched category-defining products for some of the most innovative companies in the technology sector, and is supported by the world’s most elite investors.

Meet our Leaders ›Careers

Join the Cribl herd! The smartest, funniest, most passionate goats you’ll ever meet.

Learn More ›Cribl for Startups

Whether you’re just getting started or scaling up, the Cribl for Startups program gives you the tools and resources your company needs to be successful at every stage.

Learn More ›Contact Us

Want to learn more about Cribl from our sales experts? Send us your contact information and we’ll be in touch.

Talk to an Expert ›

- Products

- Solutions

-

BY USE CASE

- Supercharge Security Insights

- Accelerate Cloud Migration

- Avoid Vendor Lock-in

- Agent Consolidation

- Slash Storage Costs

- Free Up Space for High-Value Data

- Route From Any Source To Any Destination

- Immediate Access to Archived Data

- Replay Data from Low-Cost Storage

- Reduce Log Volume & Pay Less for Infrastructure

- BY INTEGRATION

- BY INDUSTRY

-

BY USE CASE

- Resources

- Customers

- Company

- Blog

- Support

- Partners

- Download

- Pricing

- Login